A few weeks ago I went to the see the the Italian film "La Strada" by Frederico Fellini. The plot revolves around the sweetly naive, clownishly angelic Gelsomina whose family marries her off to the brutish Zampano: a cirus strong man traveling with his ramshackle one-man show from village to village. Eventually one of Zampano's drunken rampages lands him in jail and Gelsomina, free for the first time in her life seeks the advice of Zampano's impish rival known only as "The Fool" to help her choose between staying with Zampano, or fleeing with another traveling circus. Though "The Fool" never clearly offers her a path, he assures her that everything has a purpose. Even the smallest pebble resting beneath his shoe. Even Gelsomina. It is the one uplifting moment in an otherwise bleak film.

A few weeks ago I went to the see the the Italian film "La Strada" by Frederico Fellini. The plot revolves around the sweetly naive, clownishly angelic Gelsomina whose family marries her off to the brutish Zampano: a cirus strong man traveling with his ramshackle one-man show from village to village. Eventually one of Zampano's drunken rampages lands him in jail and Gelsomina, free for the first time in her life seeks the advice of Zampano's impish rival known only as "The Fool" to help her choose between staying with Zampano, or fleeing with another traveling circus. Though "The Fool" never clearly offers her a path, he assures her that everything has a purpose. Even the smallest pebble resting beneath his shoe. Even Gelsomina. It is the one uplifting moment in an otherwise bleak film.I hated it.

Nothing against the film itself. It just that I always hate it when people say, "there is a reason for everything." I realize that its supposed to be comforting and sweet, and I try not to hold it against people when they say it to me. I know their hearts are in the right place. But what they don't realize is that this kind talk is really no different from the conspiracy theorist's dark fantasies. Far from being some sort of profound wisdom, stating "everything has a purpose" is nothing more than the sentimentally optimistic side of the coin to the conspiracy theorist's paranoid need to impose a sinister order on a frighteningly uncertain universe.

People forget what "everything" includes. Everything means everything, including some of the most unpleasant and evil things you can possibly imagine. So when people say there are "reasons for everything" they are saying, there's a purpose behind child abuse, a meaning behind murder, a function behind genocide.

Of course they don't really mean that, but it's only intellectual laziness that keeps them confronting that very unpleasant consequence of what they say. And all too often they mean something very close to exactly that. I remember reading an article on Iraq, where a soldier was interviewed about an explosion that killed his comrade standing only feet away, but left him untouched. He replied that the experience had reinforced his belief in God's plan, stating that divine intervention is the only possible explanation for his survival. On one level he was simply asserting an unshakable faith that God had special plan for him, but on some level he had to understand he was equally asserting that God's plan was perfectly OK with his buddy being blown to a million pieces.

Like the conspiracy theorist's secret world controlling cabal, the soldier is using "divine intervention" to keep at bay what he fears most: That there is no order to the universe, that there is no good reason whatsoever why he survived instead of his buddy. To confront that fact would be to acknowledge that it could have been him; that his death could be just as random, instant, and unavoidable as his fellow soldier's was.

The arbitrary nature of mortality is a hard fact to confront and it's application isn't limited to soldiers on the front line. It can be utterly paralyzing if you look it straight in the eye and I can understand why people perform so many mental gymnastics to avoid dealing with it. What perplexes me is that those gymnastics can lead to much more dangerous and difficult places than the admittedly hard challenge of simply confronting the chaos of life head on. Like most things in life, the consequences of avoiding difficulties are usually worse than the difficulties themselves.

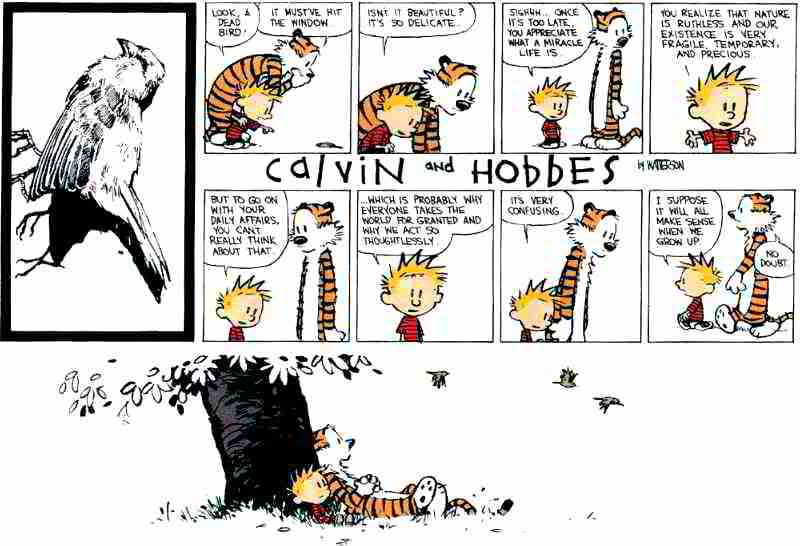

The question remains though: how do you accept the uncertainty that rules our existence and still retain the courage to move forward? I will attempt to tackle that question in Part III of this discussion, but for now - I'll leave you with a piece of wisdom from two of my favorite philosophers.